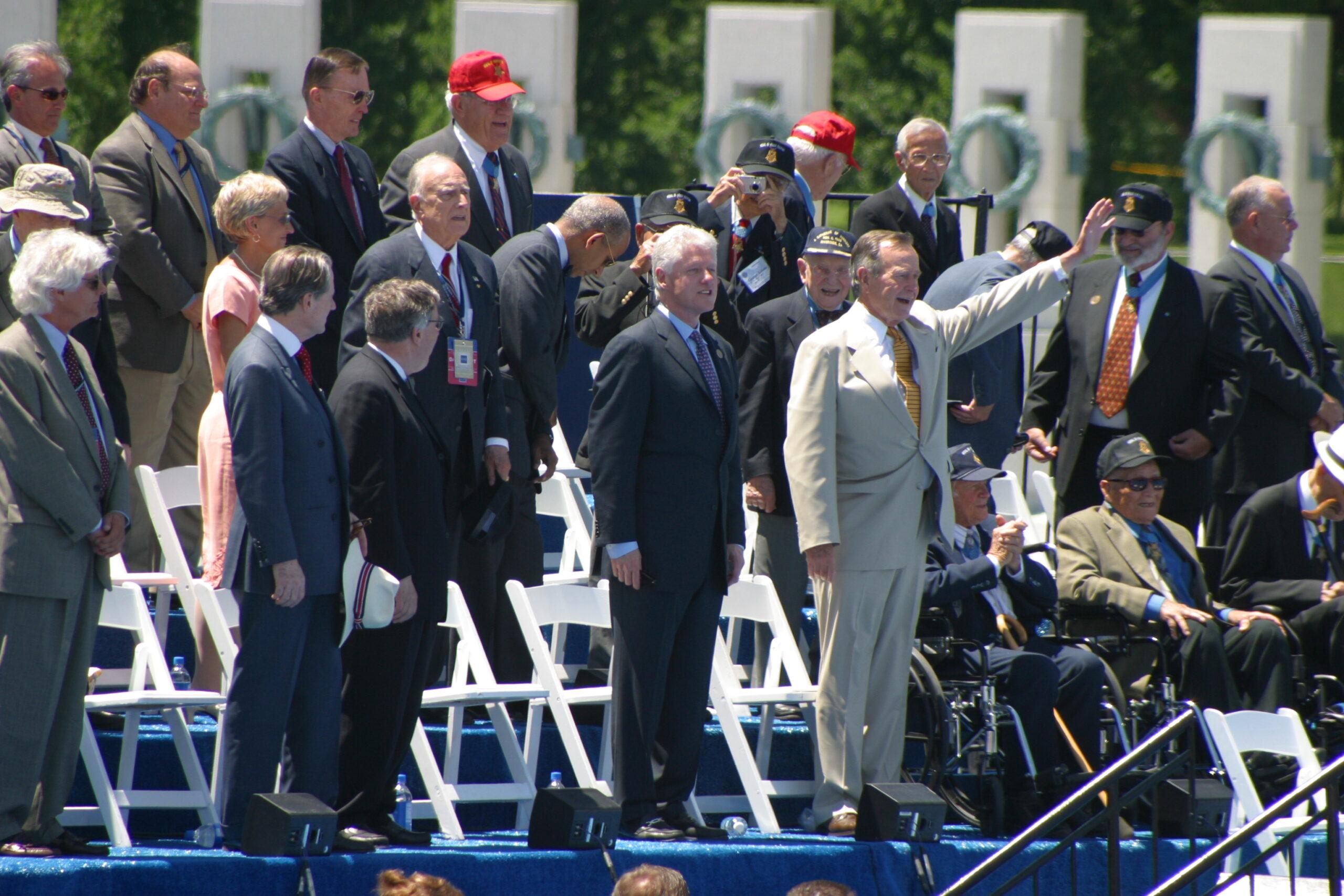

Remarks of

President George W. Bush

National WWII Memorial Dedication

May 29, 2004

I’m honored to join with President Clinton, President Bush, Senator Dole and other distinguished guests on this day of remembrance and celebration. General Kelley, here in the company of the generation that won the war, I proudly accept the World War II Memorial on behalf of the people of the United States of America.

Raising up this memorial took skill and vision and patience. Now the work is done. And it is a fitting tribute – open and expansive, like America; grand and enduring, like the achievements we honor. The years of World War II were a hard, heroic and gallant time in the life of our country. When it mattered most, an entire generation of Americans showed the finest qualities of our nation and of humanity. On this day, in their honor, we will raise the American flag over a monument that will stand as long as America itself.

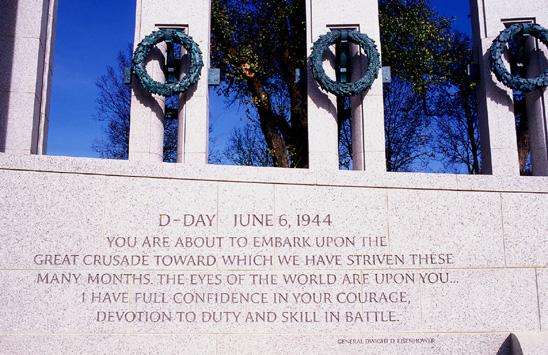

In the history books, the Second World War can appear as a series of crises and conflicts, following an inevitable course from Pearl Harbor to the coast of Normandy to the deck of the Missouri. Yet, on the day the war began, and on many hard days that followed, the outcome was far from certain. There was a time in the years before the war, when many earnest and educated people believed that democracy was finished. Men who considered themselves learned and civilized came to believe that free institutions must give way to the severe doctrines and stern discipline of a regimented society.

Ideas first whispered in the secret councils of a remote empire, or shouted in the beer halls of Munich, became mass movements, and those movements became armies. And those armies moved mercilessly forward, until the world saw Hitler striking in Paris and U.S. Navy ships burning in their own port. Across the world, from a hiding place in Holland to prison camps of Lausanne, the captives awaited their liberators. Those liberators would come, but the enterprise would require the commitment and effort of our entire nation.

As World War II began, after a decade of economic depression, the United States was not a rich country. Far from being a great power, we had only the 17th-largest army in the world. To fight and win on two fronts, Americans had to work and save and ration and sacrifice as never before. War production plants operated shifts around the clock. Across the country, families planted victory gardens – 20 million of them – producing 40 percent of the nation’s vegetables in backyards and on rooftops. Two out of every three citizens put money into war bonds. As Colonel Oveta Culp Hobby said, this was a people’s war, and everyone was in it.

As life changed in America, so did the way that Americans saw our own country and its place in the world. The bombs at Pearl Harbor destroyed the very idea that America could live in isolation from the plots of aggressive powers. The scenes of the concentration camps, the heaps of bodies and ghostly survivors, confirmed forever America’s calling to oppose the ideologies of death.

As we defended our ideals, we began to see that America is stronger when those ideals are fully implemented. America gained strength because women labored for victory in factory jobs, cared for the wounded, and wore the uniform themselves. America gained strength because African-Americans and Japanese-Americans and others fought for their country, which wasn’t always fair to them. In time, these contributions became expectations of equality. And the advances for justice in post-war America made us a better country. With all our flaws, Americans at that time had never been more united. And together, we began and completed the largest single task in our history.

At the height of conflict, America would have ships on every ocean and armies on five continents and, on the most crucial of days, would move the equivalent of a major city across the English Channel. And all these vast movements of men and armor were directed by one man who could not walk on his own strength. President Roosevelt brought his own advantages to the job. His resolve was stronger than the will of any dictator. His belief in democracy was absolute. He possessed a daring that kept the enemy guessing. He spoke to Americans with an optimism that lightened their task. And one of the saddest days of the war came just as it was ending, when the casualty notice in the morning paper began with the name Franklin D. Roosevelt, commander in chief.

Across the years, we still know his voice. And from his words, we know that he understood the character of the American people. Dictators and their generals had dismissed Americans as no match for a master race. FDR answered them. In one of his radio addresses, he said, “We have been described as a nation of weaklings, playboys. Let them tell that to General MacArthur and his men. Let them tell that to the boys in the Flying Fortresses. Let them tell that to the Marines.”

In all, more than 16 million Americans would put on the uniform of the soldier, the sailor, the airman, the Marine, the Coast Guardsman or the merchant mariner. They came from city streets and prairie towns, from public high schools and West Point. They were a modest bunch, and still are. The ranks were filled with men like Army Private Joe Seccato. In heavy fighting in France, he saw a good friend killed, and charged up a hill,

determined to shoot the ones who did it. Private Seccato ran straight into enemy fire, killing 12, wounding two, capturing four, and inspiring his whole unit to take the hill and destroy the enemy. Looking back on it 55 years later, Joe Seccato said, “I’m not a hero. Nowadays they call what I did road rage.” This man’s conduct that day gained him the Medal of Honor, one of 464 awarded for actions in World War II.

Americans in uniform served bravely, fought fiercely and kept their honor, even under the worst of conditions. Yet they were not warriors by nature. All they wanted was to finish the job and make it home. One soldier in the 58th Armored Field Artillery was known to have the best kept rifle in the unit. He told his buddies he had plans for that weapon after the war. He said, “I want to take it home, cover it in salt, hang it on the wall in my living room so I can watch it rust.”

These were the modest sons of a peaceful country, and millions of us are very proud to call them “Dad.” They gave the best years of their lives to the greatest mission their country ever accepted. They faced the most extreme danger, which took some and spared others for reasons only known to God. And wherever they advanced or touched ground, they are remembered for their goodness and their decency.

A Polish man recalls being marched through the German countryside in the last weeks of the war, when American forces suddenly appeared. He said, “Our two guards ran away. And this soldier with little blond hair jumps off his tank. ‘You’re free,’ he shouts at us. We started hugging each other, crying and screaming. God sent angels down to pick us up out of this hell place.”

Well, our boys weren’t exactly angels. They were flesh and blood, with all the limits and fears of flesh and blood. That only makes the achievement more remarkable –the courage they showed in a conflict that claimed more than 400,000 American lives, leaving so many orphans and widows and Gold Star mothers. The soldiers’ story was best told by the great Ernie Pyle, who shared their lives and died among them. In his book, Here’s Your War, he described World War II as many veterans now remember it.

“It’s a picture,” he wrote, “of tired and dirty soldiers who are alive and don’t want to die; of long, darkened convoys in the middle of the night; of shocked, silent men wandering back down the hill from battle; of jeeps and petrol dumps and smelly bedding rolls and C-rations; and blown bridges and dead mules and hospital tents and shirt collars greasy black from months of wearing; and of laughter, too; and anger and wine and lovely flowers and constant cussing. All these it is composed of, and of graves and graves and graves.”

On this Memorial Day weekend, the graves will be visited and decorated with flowers and flags. Men whose step has slowed are thinking of boys they knew when they were boys together. And women who watched the train leave and the years pass can still see the handsome face of their young sweetheart. America will not forget them either. At this place, at this memorial, we acknowledge a debt of long standing to an entire generation of Americans – those who died, those who fought and worked and grieved and went on. They saved our country, and thereby saved the liberty of mankind.

And now I ask every man and woman who saw and lived World War II, every member of that generation, to please rise, as you are able, and receive the thanks of our great nation.

May God bless you.